By Calogero Bellanca (University La Sapienza, Roma)

When one begins a reflection on the study of a cathedral, tangible expression of faith, history and art, and, in particular, regarding a complex architectural and historical-artistic reality as the one in Palermo, one is initially surprised but soon after is drawn into the study of it.

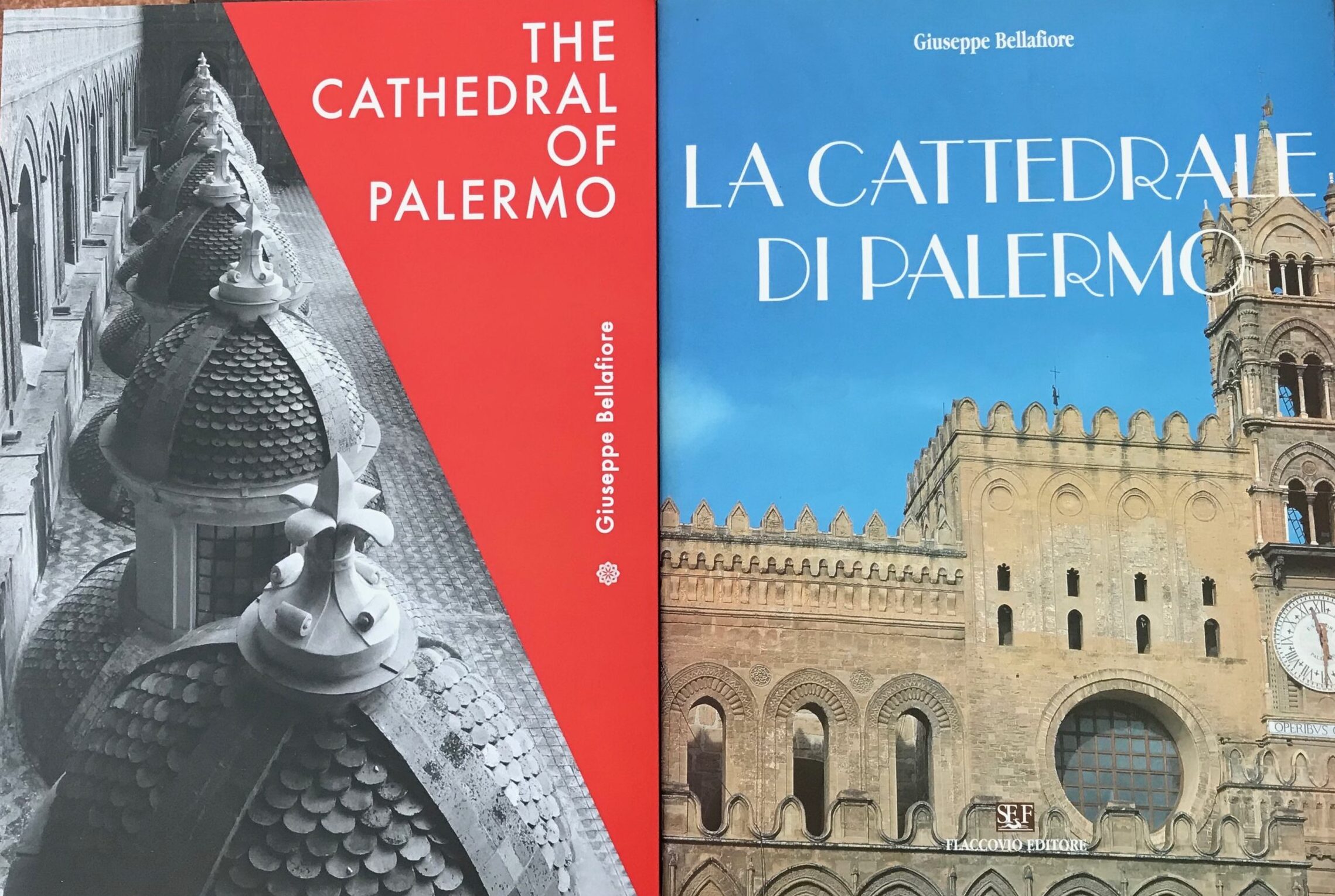

The volume of Giuseppe Bellafiore, was published in 1976 for the first time and then re-edited in 1999. It is now published in English and is the result of the decennial studies the author dedicated to this monument, as well as to many others of the city of Palermo.

The book opens remembering the history of the monument: from the buildings pre-existing the gualterian church, to the cathedral of the Norman era, then to the royal and archiepiscopal cemeteries, with the crypt, until the first metamorphosis of the external space (XVI century and first half of the XV century) comprehending the belfry on the western tower and the other bell towers.

From these early annotations it is possible to notice how in Palermo the constructors of the Norman era adopted the criteria of modifying a cross plant in a large rectangular structure, divided into two parallel zones (titulus an anti-titulus) leaving the sanctuary in semi-darkness.

“The originality of the Cathedral of Palermo consisted in, other than of the singular arrangement of the presbyterial space, of the introduction of pillars composed of four shafts of columns each”. From the examination of these constructive characters one can clearly see once again how Sicily was defined as depositary of its own figurative and architectural culture expressed on one side by the byzantine influence, and on the other from Arabian linguistic and decorative language coming from the Fatimid Egypt. The Normans absorbed both influences in a figural syncretism expressed in various monuments of high architectural and historical-artistic quality.

One may consider the examples of the of the three main cathedrals of the Norman period: Cefalù, Monreale and Palermo. The Palermo’s Cathedral of the Norman period dominated the urban landscape of the medieval city with its fortified walls, its plastic decorations and most of all with its balanced symmetry.

In this book specific attention is given to the various fourteenth century insertions and in particular to the single-lancet windows and the inserted blind arches which were later transformed into two-light windows, twenty per side. This insertion respected the pre-existing decoration of the archivolts and pendentives.

As for the Cathedral of Gualtiero and for the first additions, the considerable iconographic documentation studied and presented by the author, is very helpful.

One may recall the prints of Antonio Grano of 1686, two paintings kept in the Diocesan Museum, the first from 1575 and the second from the eighteenth century, and more over an incision of Arcangelo Leanti published in 1761.

In the period between 1460 and 1567, Bellafiore highlights a new relationship with the city with the configuration of the “loggia” and the renovation of the urban space in front. At the same time, he describes the Gagini’s retable which introduces a substantial change in the space of the apse, and a re-definition of the surface of the walls with the whitewashing of the internal surfaces of the church.

The transformations and additions continued from the late sixteenth century to half of the eighteenth century. After the “concealment” of the main apse with the retable, the two lateral apses were also remodelled and coated with stuccoes.

The chapels of the right nave were “rebuilt” with heavy decorations. At the same time the northern “portico” was added along the left nave, in substitution of some chapels. This study demonstrates how, during the seventeenth and eighteenth century, various ephemeral arrays dedicated to Santa Rosalia’s festivities, coronations and ceremonies, were carried out. One of the first marble decorations realized in the Santa Rosalia’s Chapel (1626), that the City Senate wanted and which was destroyed by the late eighteenth century “modernizing” renovations, is attributed to Smiriglio.

In the first years of the eighteenth century it was possible to witness a re-invention of the internal spatiality; the interventions were only aimed at the conservation of the wall structures, although these were reshaped in their entirety. In fact, the wooden ceilings of the lateral naves were concealed and substituted with rib vaults. The decorative expression of the late Renaissance and of the Baroque era, changed the internal spatiality.

The study proceeds with the description of the other transformations carried out in the period between 1781 and 1801, in which the pre-existent architectonic structure endured the insertion of a late Baroque dome, together with various blind arches, grotesque figures and merlons, while the interior was re-shaped in the new rigorous repartition of the central nave and of the lateral ones.

However, the cycle of the renovations of the monument was not concluded and, as well as some other European cathedrals, the restorations and liturgical adjustments continued until now.

Thus, in the middle of the nineteenth century, between 1840 and 1844, during the time of the great “in style” interventions all over Europe, the belfries were added to the western tower. This additions, with the dome, were some stratifications as expression of its time.

One can observe how this cathedral, as well as other monuments, went through a very long restoration period that also included projects, some realized and others never carried out, such as the substitution of the dome with another hemispheric construction in Norman style, designed by Francesco Valenti in 1932.

Recalling a statement by Guglielmo De Angelis d’Ossat, reformations and contrasts had happened and according to Renato Bonelli “the aim was to bring back the monument to its own determined historic world, ideally replacing it in the environment where it had arisen and considering its relations with the culture and the taste of its own time”. Moreover, the restoration was intended to bring back the Cathedral, ignoring the true formal qualities which determine the singularity. It arrived to the point where reconstructions which altered the structure and the form in the name of an abstract coherence of style, were legitimated.

The study devotes the diverse methodologies of the history of architecture: from formalistic, to iconological, all the way to take on the lingual structuralism necessary for the comprehension of the architectural programming that is always studied finding once more the procedures that generated and inserted them in the different historical periods. This way the author while still addressing the structures, attempts to let dialogue the different instances, or rather he exceeds Adolfo Venturi’s claims where architecture is evaluated in terms of images and it approaches the thoughts started by Gustavo Giovannoni and his disciples’ Roman school, in particular Giuseppe Zander, reading from the interior the reality of Architecture with “rilievi”, notes on technical methods and the intrinsic reasons of construction. To these methodological acquisitions the reception of Renato Bonelli’s recall to the poetic and aesthetic sense necessary for the comprehension of the organism.

In this way this volume inserts itself in the grand stream of Italian and European architectural history that has produced from the beginning of the twentieth century with the studies of G.B, Giovenale, L. Beltrami, A. Prandi, ecc…, fundamental monographs that were increased with contributions from the post second world war years and more in particular during the Seventies and Eighties, even with those diverse angles, marked by disciplinary and interdisciplinary contributions and relationships. To this end it seems appropriate to remember certain studies that were dedicated to monuments scattered in the different districts in our country: from R. Bonelli, Il duomo di Orvieto e l’architettura italiana del duecento e trecento, Roma 1972, II ediz.,2003. A.C. Quintavalle, La cattedrale di Parma e il romanico Europeo, Parma 1974,A. P. Sanpaolesi, Il duomo di Pisa e l’architettura romanica toscana delle origini, Pisa 1975 and still AA.VV., la Basilica di San Petronio, Bologna 1983 and 1984, AA.VV., la Basilica di Sant’Eustorgio in Milano, Milano 1984, and AA.VV., Il duomo di Trento, Trento 1992, up to the most recent volume, La cattedrale di Spoleto. Storia, arte, conservazione, Milano 2002.

Bellafiore’s work demonstrates how the historic-critical knowledge of a monument of undoubted exceptionality and complexity such as the cathedral of Palermo, is the result of direct, visual, cognitive of a great deal of architecture cited and examined in the course of the years together with the study of the different sources, is fundamental to reach solid and articulated definitions. Although the guide was written several years ago, it is far from dated and instead shows that the summary of architectural history is not always easy and remains always a valid source for the progression of studies and the education of younger generations of scholars of architecture, of its history and its preservation.

Share on:

Address: Via XX Settembre, 53 – 90141 Palermo

Telephone: +39 371 1897997

Email: susannabellafiore@gmail.com

Credit card

Paypal

Copyright 2021 Susanna Bellafiore Editore P.IVA: 06223200822 – Casa editrice a Palermo – Privacy e Cookie Policy